My last three posts have looked into various aspects of NH’s

Renewable Portfolio Standard (RPS). I presented the

basic workings of the program, discussed

renewable energy credits (RECs)

and REC prices and, most recently, looked at money

flow and costs of the RPS program. The

program originally included a steady increase in the renewable energy (RE)

requirement year on year; however, to reduce costs to electricity customers, some

big adjustment in the requirements have been made over time to accommodate changing

market conditions and the non-availability of RECs in specific classes. This

post discusses the implications of some of those changes as NH gets back on

track to meet its 2025 RPS goals.

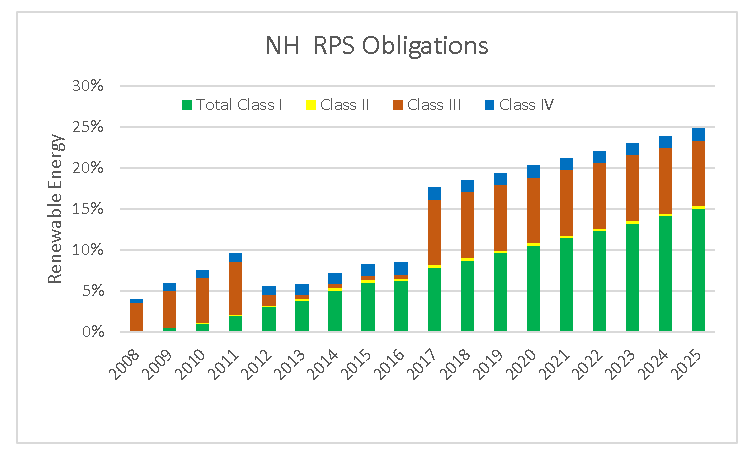

As noted previously, there are four classes of renewable energy in the NH RPS. Class I is for newer RE technologies, such as wind or ocean energy, and RE operations that have been commissioned since 2006. Class II is a special carve out for solar power. Classes III is for the older biomass operations, which include electricity generated from burning landfill methane or wood, and Class IV is for smaller hydro operations that were established prior to the end of 2005.

As noted previously, there are four classes of renewable energy in the NH RPS. Class I is for newer RE technologies, such as wind or ocean energy, and RE operations that have been commissioned since 2006. Class II is a special carve out for solar power. Classes III is for the older biomass operations, which include electricity generated from burning landfill methane or wood, and Class IV is for smaller hydro operations that were established prior to the end of 2005.

NH has an important forestry industry and eight wood-burning plants that generate electricity. Right from

the start of the RPS program, a large Class III requirement was put in place to support these wood-burning

plants; however, from 2012 to 2016,

the amount of RE from Class III was significantly curtailed to cope with the

shortage of Class III RECs and to mitigate the cost of the shortage for ratepayers.

The reason for the shortage was that the Connecticut (CT) REC market had high

prices and had sucked in RECs from all over New England, including NH Class III

RECs that qualified as CT Class I RECs. With limited NH Class III available, electricity

suppliers would have been compelled to pay the Alternative

Compliance Payment (ACP) instead, increasing costs to ratepayers.

In 2016 the NH Public Utilities Commission (PUC) held hearings on the topic and were informed that the REC market had changed, that CT REC

prices had decreased, and there was testimony from the biomass coalition that

sufficient Class III RECs would be generated and be available for purchase.

Electricity suppliers weren’t convinced and, after deliberation, the PUC commissioners

ruled to return the Class III requirement from 0.5 to 8% to put

NH back on track to meet its RE ramp-up to meet the 2025 obligation, as shown

in the chart below.

For 2017, the specific RE class requirements and associated

ACPs are presently as follows:

Given this big ramp from 0.5% to 8%, I though it worth

taking a closer look at the Class III REC market and the availability of

biomass RECs to meet this requirement.

Let’s start with some basic calculations. Approximately

11,000,000 MWh of electricity are supplied annually to ratepayers and customers

in NH. It follows that an 8% Class III requirement therefore needs to

provide 880,000 MWh of electricity from pre-2006 biomass operations. The REC

requirement is therefore also 880,000 MWh. That is a boatload of RECs – and the

question is: Can that many RECs be generated from this source?

I then found the list of registered Class III providers at the NH PUC, which is provided below.

Closer examination of this list brings to light the

following:

- There are 20 registered Class III operations, providing a total generating capacity of 137 MW. Most of the operations (13 of 20) are from out of state.

- Only three of NH’s eight wood-burning plants (highlighted in green) are registered as Class III producers: the rest, such as the large Berlin biomass operation, appear to be registered as Class I producers.

- Of the 137 MW of Class III capacity available, the NH wood-burning plants only provide 56 MW, or 41% of the total capacity: the rest comes from in-state and out-of-state landfill methane operations.

- If we include the NH landfill methane operations (highlighted in grey) with the NH-based wood plants, only 68 MW, or 49% of the total capacity, is provided by NH-based plants: the rest is from out-of-state landfill gas operations in RI, NY, and VT.

I

found all of this surprising because my understanding is that the original

intent of including the Class III category in the NH RPS was to support NH

biomass operations. Instead, in its

present form, it seems to be doing a lot to support out-of-state landfill operations.

Let’s return briefly to some calculations. If we take that 137 MW of Class III generating capacity and assume that the generating plants are operational for 90% of the time (see my I’ve Got the Power post for a discussion of capacity factor and the difference between generation capacity and energy), we can determine how much electricity should be generated over one year: 137 MW x 0.9 x 365 days x 24 hours/day. This calculation gives 1,080,108 MWh or RECs. This is a useful result because it suggests that there could be production of sufficient RECs to cover the 880,000 that we need. In fact, the calculation suggests that we might potentially have an excess of Class III RECs, which hopefully will drive their prices down and save money for NH ratepayers.

REC producers in New England are required to register and

file their REC production data with the New

England Power Pool Information System (NEEPOL GIS). Some

of the data is available to the public. I

noted that in 2015 and 2016, 1,005,258 and 924,716 NH Class III eligible RECs

were produced, respectively. This is right in line with my calculation of 1,080,108

RECs. Historically, there seem to be sufficient Class III RECs to meet NH’s

needs.

However, availability does not obligate producers to sell

into the NH REC market. They could, especially if prices are high, elect to

sell, as in previous years, into other markets, such as the CT Class I market.

If insufficient Class III RECs are available, prices will quickly rise close to

the Class III ACP cap of $ 45. As a biomass RE generator, that is what I would

want and I might choose to direct some of my RECs to a different market to support higher NH Class III REC prices. This is a direct

consequence of our inconsistent and changing REC market in New England. It

provides opportunities for good traders to play off the differences between

markets—and it makes perfect business sense to do so.

However— and this is a big HOWEVER— the calculation of a

surplus assumes that all operations run 90% of the time, that there are no major

shut downs at any of the larger facilities, and that biomass REC producers

don’t elect to sell Class III in other eligible markets. Another complicating

factor is that there is legislation, known as SB129 presently making its way through the NH General Court that makes

important modifications to the RPS program, especially in the Class III

category. Just last week, the NH House approved a change in the RPS law that

promotes NH biomass in two ways:

- It would put a 10 MW limit on the size of landfill methane operations that qualify for Class III RECs. This change appears to be directed at eliminating some of the large out-of-state landfill operations from RI and NY that have been participating in the NH Class III market.

- The ACP for Class III RECs would be increased to $ 55, which should increase the REC prices in the case of a Class III REC shortfall.

If we go back to the list of Class III operations above, I

have highlighted two potential operations that may not qualify for the

production of Class III RECs under the new 10 MW limit: the first is the large Johnston

landfill in RI, highlighted in orange, and the second, highlighted in blue, is the

Seneca landfill in NY (if its combined output is considered). If both of these landfills are excluded, this would

lead to a 36.3 MW reduction in Class III REC generation capacity, which

represents an overall decrease of 26%. This would result the production of only

794,000 RECs, which is short of the 880,000 that NH needs in Class III. What

are the consequences of this shortfall? This

means that the prices for Class III will climb to close to the value of the price

cap (the ACP) and the shortfall will be made up by utilities having to pay the

ACP.

The next question is: What are the implications of these

changes to NH ratepayers? Let’s turn again to some calculations and assume that

those 794,000 RECs sell for 90% of the $ 55 ACP, or $ 50, and that the

shortfall of 86,000 is paid in as the $ 55 ACP. In this case, we can calculate that

the Class III requirement of 8% and the higher ACP could cost NH electricity

customers some $ 44 million annually. If we apply this amount over the 11

billion kWh of electricity sold annually in NH, the rates can be expected to

increase by 0.4 cents/kWh. For a NH residential customer using 600 kWh per

month, this could result in an annual electricity cost increase of about $ 30.

I did extend this calculation to determine a total cost for the

RPS program for 2017 based on lower Class I REC prices and some significant

assumptions on REC availability and prices in the other classes. My

calculations led to an RPS cost of approximately $77 million which is 4.7% of the $1.7 billion I’m assuming

will be paid for electricity by NH ratepayers in 2017 (based on $150/MWh

($0.15/kWh) retail rate and 11 million MWh of electricity). This is a

significant increase over the 2.6% value I calculated for the 2015 RPS program in

my previous post.

Now, bear in mind that these are rough back-of-the-envelope

calculations; they do, however, give a sense of the potential implications for

NH ratepayers of the Class III ramp up to 8% combined with the proposed RPS

SB129 legislation. Perhaps I am dead wrong in my assumptions. Maybe the Class

III generators will produce RECs beyond their rated capacity, perhaps not all of

those highlighted out-of-state landfills will be excluded from the Class III

list, and perhaps the Class III generators will choose not to sell any of their RECs into

the CT Class I market. In this case, a surplus of Class III RECs will be

produced, prices will be much lower, and the costs to NH ratepayer will be reduced.

There is even the possibility that the PUC could jump in again to ratchet down

that Class III requirement, as they have in previous years. Regardless, this is

certainly food for thought as the SB129 legislation makes its way through the

lawmaking machine and onto the Governor’s desk.

This is a complicated matter and it presents a huge dilemma

for legislators, regulators, and the wood-burning plants in NH. On one hand, as

pointed out in my post, Between

a Rock and Hard Place, the NH wood-burning plants absolutely need the REC

revenue and higher REC prices to survive. In fact, one such plant, the

Indeck Energy plant in Alexandra, recently closed down due to low wholesale electricity and REC

prices. Alternative forms of electricity generation are also very important and

wood-burning capacity helps to reduce our dependence on natural gas-fired

generation. But, on the other hand, legislators and the PUC commissioners need

to weigh the cost of the REC-based subsidies of the biomass industry against

costs to ratepayers. There are no easy answers and these are difficult

decisions to make.

Feel free to weigh in on this issue because it is a

surprisingly important one. In the meantime, do your part to reduce our need

for electricity from any generation source by remembering to turn off the

lights when you leave the room.

Mike

Mooiman

Franklin

Pierce University

mooimanm@franklinpierce.edu