In my last post, I looked at the big picture of energy

supply and consumption in New Hampshire, as well as some gross measures of

energy efficiency (EE), viz., energy intensity and energy use per capita. The

data indicated that we are making progress, but that we have a long, long way

to go before we can consider ourselves energy efficient. In this post, I take a

look at NH’s EE ranking and some important policy developments that will help

promote EE in the state.

The American Council on an Energy Efficient Economy (ACEEE)

produces an annual scorecard that ranks the states on their EE initiatives and

progress. The map below shows the state rankings in the most recent scorecard report. The ranking is done by grading each state’s

utility EE programs, transportation initiatives, building energy codes, state

government initiatives, and combined heat and power programs. NH’s ranking is

in the midrange at # 21: we are surrounded by New England states with much

better rankings, including Massachusetts, which, along with California, hold

the number 1 spot.

A closer look at the NH’s

scorecard is enlightening. The figure below shows specific data regarding

various scorecard components compared with those of NH’s immediate neighbors.

As you can see, NH’s scores were run-of-the-mill in the areas

of utility programs, building codes, and state initiatives, and poor in

transportation, appliance, and combined heat and power initiatives. The

scorecard report does note that the state took a big step forward by approving

new energy-savings targets for 2018 to 2020, but also remarked that NH could improve

considerably in the transportation and combined heat and power sectors. Our

neighbors are clearly doing more in almost all categories.

The other type of EE initiatives are those in which we

voluntarily participate by making non-mandated but important EE decisions; for

example, the replacement of an incandescent or CFL lightbulb with a more

expensive but more energy-efficient LED bulb.

The third driver for EE is energy prices. We are very basic

creatures and respond to financial incentives, so if energy prices are high, be

it electricity, natural gas, or gasoline, we generally take active measures to

reduce our energy expenditure by driving less, buying more fuel-efficient vehicles,

or putting on a sweater and turning down the thermostat. One might argue that

high energy prices are just a driver of our voluntary actions; however, I see

them as different because there is often an altruistic/it’s good for the planet/right-thing-to-do

component to voluntary action. And if you can save boatloads of money by doing

the right thing for the planet, more power to you. (Or perhaps that should be less power to you?)

For the remainder of this post, I review utility-run EE

programs in NH. These are a combination of mandated and voluntary actions. The

utilities are mandated to offer them, but we, as home or business owners, voluntarily

participate in them, but, in doing so, we also have to open our wallets to pay

for our part of these investments.

Since

2002, NH has had a formal utility-run

program to promote EE investments in NH, known as the Core Energy Efficiency

Program. This is a New Hampshire Public Utility Commission (NHPUC)-mandated

program with required participation by the electrical and natural gas utilities.

The utilities collaborate in their efforts to provide savings, information, incentives,

and assistance in the implementation of EE investments to their ratepayers,

which include municipalities, homeowners, and industrial and commercial

operations. Information about the program is reported on the NHSaves website,

which is a good place to start looking for information about energy savings and

EE if you are a NH ratepayer. The program is directed at both the electrical

and natural gas utilities and requires savings in both.

The NHSaves program has many features and offers a lot of

services to realize energy savings. Quoting directly from the 2017

New Hampshire Statewide Energy Efficiency Plan, the elements of the program

include:

- “Working with Home Energy Raters and building contractors, to incent the construction of highly efficient homes that use 15-30 percent less energy than a standard new home.

- Incentivizing insulation, air-sealing and other weatherization measures performed by qualified private contractors to reduce a homeowner’s heating fuel use by more than 15 percent on average.

- Providing insulation, air-sealing and other weatherization measures to low-income families, saving them hundreds of dollars per year on energy costs, though a collaboration with the NH Office of Energy and Planning’s Weatherization Assistance Program and New Hampshire’s six Community Action Agencies.

- Partnering with over 100 New Hampshire appliance retailers and suppliers across the state to help customers purchase highly efficient appliances such as refrigerators, clothes washers and room air conditioners, saving 10-20 percent of the energy they would have used if they had purchased standard efficiency models.

- Partnering with over 100 lighting retailers and suppliers across the state to reduce the barriers for New Hampshire customers to purchase energy efficient lighting measures that can save between $30 to $80 over the lifetime of a single product.

- Working with qualified private contractors to help businesses and non-profits identify and install more efficient lighting, controls, motors, HVAC equipment, air compressors and industrial process equipment.

- Focusing on municipalities to help save energy in public buildings, reducing overall costs to taxpayers and making public spaces a model for efficiency improvements.”

To date, the goals of the NH program have been modest and

the annual energy savings have been small—of the order of 0.5% of NH total

energy consumption. Our neighboring states have been more aggressive in their

savings; for

example, in 2015, RI, MA, VT, and ME had savings of 2.91%, 3.74%, 2.01%,

and 1.53% of their 2015 retail sales, respectively.

Even though NH’s annual savings have been relatively small,

these small savings, year on year, have accumulated over time. It

has been estimated that, since the start of the Core program, customers

have saved over $1.9 billion and reduced electricity consumption by 12 billion

kWh and natural gas use by 24.5 million MMBtus (million BTUs). The Core

program, by most measures, has been a successful one.

These accumulated savings are great, but there is a cost for

the program that NH ratepayers fund. The

2016 budget was ~$24 million for the electrical EE programs and ~$7 million

for the gas programs. The electrical component has been funded by part of the

Systems Benefit Charge (SBC) paid by each electrical ratepayer (in

2017, the EE portion will be 0.198 cents/kWh

of the 0..354 cents/kWh SBC charge averaged across the four utilities), money

from the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI) auctions that are

distributed to the NE states, and from the ISO-NE capacity market. The natural

gas savings program has been funded through the local distribution adjustment

charge (LDAC) paid by natural gas users. Typically, the split in funding for

the electrical program has been 70% from SBC funds, 19% from RGGI, 10% from the

forward capacity market, and 1% from

carryover and interest, whereas the natural gas savings program is funded

completely from the LDAC charge.

It is important to appreciate that all ratepayers pay their

share towards the program, but only those that elect to participate benefit

directly and reap the big savings. To actively benefit from this program and

reap the rewards requires you, as the ratepayer, to make an upfront EE investment.

The amount that you have to pay depends on your utility, class of service, and

particular type of EE investment. Even though there is a requirement for an

upfront investment, the utility-run EE programs have been popular: there have

been waiting lists and money to fund EE investments has run out before the end

of each year.

Even if you don’t participate directly, you, along with other

non-participating ratepayers, benefit indirectly because reduced energy

consumption, regardless where it comes from, benefits us all. It improves the resiliency

of our energy-delivery systems because less energy has to be sourced, it keeps

our costs down because fewer power plants have to be built, our resources last

longer, less pollution results, greenhouse gas emissions are reduced, local

jobs are created, and, as

noted in my previous post, there is a cascade of other benefits that results

from EE investments.

The Core program is well run and carefully administered, and

a great deal of effort is expended in evaluating its effectiveness. It is

overseen by the NHPUC, but is run by the electrical and natural gas utility

companies that are required to submit a joint annual plan and budget. The joint

administration and shared marketing resources through the NHSaves program

ensures consistency and best practice implementation across all utilities. Each

utility is required to provide quarterly and annual reports and is subject to

annual financial audits and independent certification of savings. The program is a serious endeavor and is continually

reviewed. THE

NHPUC has over 130 reports evaluating the effectiveness of EE programs in

NH and NE. I consider this to be an important and well-run, documented,

audited, and verified initiative.

As part of their administration of the EE program, the

utilities carefully vet the projects that are considered and each undergoes a thorough

cost-effective screening. Each program is required to have a benefit-to-cost

ratio above one. The costs and benefits are over the lifetime of the project (which

vary depending on the nature of the project); costs include both the utility

and ratepayer contributions. The specific benefit:cost goals laid out in the

2017 plan are shown in the table below.

As mentioned, the utilities report annually on their EE

programs, recording what was spent and what the benefits were. I have

summarized some key findings from the 2015 reports in the table and bullet

points below:

- Eversource, with the largest number of customers in NH, spent the most on EE programs.

- There are variations from utility to utility, but the end users (homeowners, commercial, industrial and municipal) are paying, on average, 45% of the costs of EE investment; the utility pays the other 55% out of their funds allocated for EE.

- Homeowners are paying, on average, 37% of their EE investments.

- The lifetime benefit/cost ratio is an average of 2.2, which means that, for every $ invested in EE, NH reaps over $2 in benefits in terms of energy savings.

Overall, the cost of EE investments in NH through the Core program has

been estimated to be 3.7 cents/kWh. If we

had spent this money on just buying more electricity, we would have paid the

retail price of about 16 cents/kWh. The natural gas savings are similar:

$0.336/therm for EE vs. $0.81/therm for purchase. In short, investing in EE is

a bargain.

The challenge with the Core program is that, while it has

been popular, funding has been limited and a lot of deserving EE projects have not

yet been implemented. To support more EE savings and meet the objectives

of NH’s

10-year Energy Strategy, the NHPUC has recently approved a new statewide

utility-run EE policy, known as the Energy Efficiency Resource Standard (EERS).

This program boosts the annual goals for energy efficiency and increases funding

available for EE investments. It kicks in at the start of 2018 and requires utilities

to increase their annual energy savings. The EERS program was developed with significant

stakeholder involvement, ranging from environmental lobbying groups, utilities,

state representation, community action groups, and other energy-related

non-profits. The program will be overseen by NHPUC with input from stakeholders

and will be jointly administered by the utilities, as with the Core program.

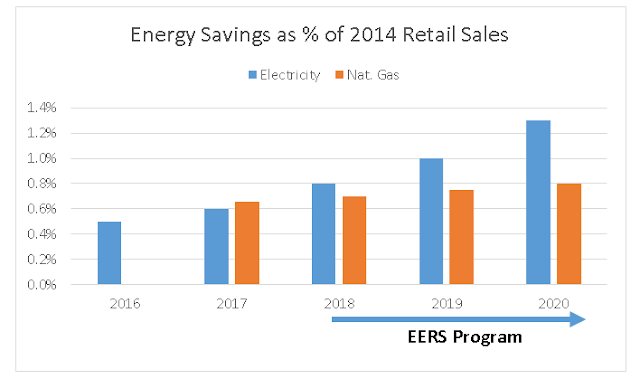

The annual goals for the new EERS program, and how they

compare with the recent Core program goals, are shown in the figure below.

It is good to see the annual savings increase: over the next

four years (2017 to 2020), there will be a cumulative savings of 3.1% of

electricity and 2.25% of natural gas (compared with 2014 consumption). But,

again, I need to note that, compared with our neighbors, these goals are rather

humble: the

average annual electrical savings increases are 2.1% for Vermont, 2.9% for

Massachusetts, 2.4% for Maine, and 2.6% for Rhode Island.

The

EERS plan also has the following features:

- Instead of the two-year planning and implementation cycles used in the Core program, the EERS program will use a three-year cycle.

- Funding for EE investments will more than double over the next few years. In 2016, the budget for EE investments was $31 million; in 2020, it proposed to be $74 million.

- The money for these increased EE investments will come from an increase in the SBC and LDAC components of the utility bill. The average SBC and LDAC in 2017 will be 0..354 cents/kWh and 4.95 cents/therm, increasing to 0.821 cents/kWh and 6.91 cents/therm in 2020, respectively. This will result in a $2.70 monthly increase in the electrical bill for a ratepayer using 600 kWh per month. Overall, the EERS program will contribute to a 2 to 3% increase in NH utility bills from 2017 to 2020.

- To compensate utilities for the lower energy sales and lost revenue associated with EE, a lost revenue adjustment mechanism (LRAM) will be implemented. This is new and is built into the SBC rate increase.

- As with the Core program, there are built-in performance incentives to encourage utilities to make these investments. Basically, the utilities will earn a bonus for achieving above-budget energy savings.

- The EESE Board, which is a multi-stakeholder committee that works with the NHPUC to promote energy efficiency and sustainable energy in the state, will serve as a review and advisory council.

- Evaluation, monitoring, and verification will be carried out by independent consultants.

- The low-income assistance portion of the program will increase from 15.5% to 17% of the total EE budget for the first three years.

There are, of course, objections to the EERS program. It

will increase the bills of all ratepayers across the state, but big savings

only accrue to those who participate and have the funds to foot their part of

the investment. However, bear in mind that if your neighbor makes a big

investment in EE and significantly reduces her monthly cost, you indirectly

benefit from improved energy system resiliency, lower long-term energy costs,

less pollution, etc. This is similar to the benefits that an SUV driver might derive

from drivers of EE vehicles: those drivers of EE vehicles extend the lifetime

of oil resources, reduce pollution, and keep oil prices down. Ultimately, it is your choice whether to pour

your dollars into your gas tank or into inefficient energy use in your home,

but keep in mind that you do benefit from the EE activities of others.

Should you find yourself agitated by the increase in utility

rates associated with the EERS program, I encourage you to take direct action

that undo that increase. Go through your home and find three old style

incandescent ightbulbs and change them to LED bulbs (which can be purchased for $2/bulb). The annual energy savings from these bulbs (assuming you have changed

to 10W LEDs, burning for 4 hours a day

and your average electricity use per month is 600 W) will save you 2.7% of your

electricity bill which more than relieves that phased SBC increase.

It must also be appreciated that EE presents a problem to

regulated utility companies. They are in business to sell electricity or natural

gas and thereby earn a return on their investments to pass on to their investors.

(And before you get all self-righteous about money-grabbing investors, look at

the companies in your retirement investments: you will mostly likely find some

utility companies in your portfolio, making you one of those investors. Utility

company shares have proved to be extraordinarily reliable investments with steady

returns.) When utilities are obligated to make investments in EE, this reduces

the amount of electricity or natural gas they sell, reduces revenue and profits,

and limits opportunities to make infrastructure investments on which they can

earn a return. Moreover, they have to administer these EE investments, employ staff

to run these programs, and incur costs. Generally, the utilities would not be

in favor of these programs so they need to be incentivized to participate. This

is done by compensating them for the lost sales and costs associated with the

EE program, which is built into the SBC or LDAC charges. In essence, the

utilities get to sell less of their energy commodity at higher prices.

This post has covered NH’s middle-ranking EE. We are way

behind our New England neighbors in EE, but the saving grace* is that that NH is

in the process of transitioning from the Core to the EERS program, which is an

important step forward. Required annual

energy savings will increase and EE investment budgets will more than double.

This will have utility-cost implications because NH ratepayers will see a 2 to

3% increase in their utility bills over the 2017–2020 period as a result of

these changes. However, these are good programs that make a difference and we

all benefit and, by our implementing our own simple EE actions, like changing over to LED lightbulbs, we can cancel out the effect of the rate increase. It is a far better idea to make EE investments now that reduce our exploitation of fuel

resources and reduce energy infrastructure investments. This will reduce energy

cost increases in the future.

However, to fully benefit from these programs requires

action and investment on our part. This is something that we don’t always do—even

when we know it is the right thing. I will discuss this lack of action in my

next post. In the meantime, do your bit for energy efficiency and turn off the

lights when you leave the room.

Mike

Mooiman

Franklin

Pierce University

mooimanm@franklinpierce.edu

(*Saving Grace: A fabulous tune with a great driving groove

by one of my favorites: Tom Petty. From the Highway

Companion album released in 2006. Enjoy Saving Grace.)